Introduction

A painter´s life

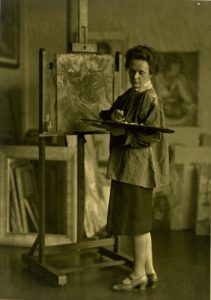

The artist Anta Rupflin, born January 27th 1895 in Pasing near Munich, is one of the long forgotten German artists of the Lost Generation. She grew up in Augsburg where she soon – in the early 20th century – began to make her way into the world of fine arts.

The first carefully executed still lifes, interiors and landscapes signed with “Toni Treu”, remained until today – one of them dated 1911. In the following years she did several landscapes in water colour as well as a series of tree studies in different techniques, which unfortunately can not be dated more precisely, but were certainly created before 1920.

Although the young artist had never attended an academy, she had received a variety of institutional and private training. Her attendance at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Munich before World War I, first with F. H. Ehmke (1878-1965) and then again around 1923 with the painter Willi Geiger, is documented, as are her private lessons with the painters Hugo Ernst Schnegg (1875-1950) around 1920/21 and Willi Geiger (1878-1971) around 1923. Finally in 1925 she was taught by Amadée Ozenfant (1886-1966) in Paris, where she also encountered the polish painter Mela Muter (1876-1967), who later should become one of Anta´s closest friends and major influencers.

Probably inspired on the one hand by the works and charisma of Hugo Ernst Schnegg, whom she had met at one of his exhibitions in Augsburg 1920/21, on the other hand through private lessons by him in 1925 and in the following years by the Polish painter Mela Muter, Anta began to thoroughly develop her painting skills. During the 50 years of her creative period she continuously developed her intense and passionate style until shortly before her death in 1987.

However the term painting in this case will have to be slightly differentiated from the usual meaning. Only during her very early phase – around 1925-23 – Rupflin painted with oil on canvas or panel. In the following period materials like paper and carton varying in size and strength dominate her Œuvre. Most of her works – at least until the mid-60s – were executed on her many travels to Tunis, Dalmatia, Italy and Spain, which explains her preference of light and portable materials. The predominant use of paper was thus due to practical reasons.

Nevertheless she did not focus solely on drawings and smaller formats during her trips, but created a significant amount of midsized to large watercolours, pastels and works in oil and/or tempera.

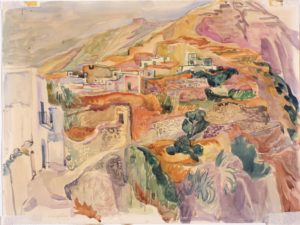

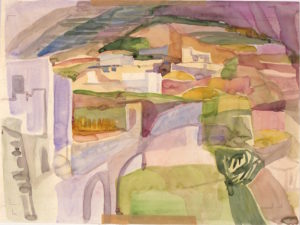

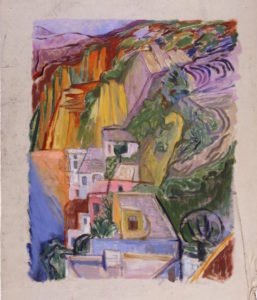

Particularly the colour has always played a major role in Rupflin´s Œuvre. Already in her early years she developed an exceptional sense for colour, as one may already notice in her very early Landscapes of Lake Constance around 1925 (L102) as well as the views over Tunis in watercolour 1930 (L349) and Positano 1933 (L360). Due to her choice of subtle, well-coordinated colouring she created an impressive atmosphere within the exceptionally vivid compositions.

During her stay in Dalmatia and the Island of Korkula in particular in summer 1938 and 39, she turned away from watercolour; instead she concentrated on very carefully executed pen and ink drawings with extraordinary handling of light and shade (L330) as well as strongly coloured pastels of landscapes (L323), which seem astonishingly abstract, almost expressive for this time in Germany. Compared with landscapes executed only a few years earlier the rapid progress in style is striking.

During the period she spent on the island of Ischia 1953 and the following year, she found her way back to watercolours. Those works, however, appear stylistically very different from the earlier ones. She may have found inspiration for her new way of stylising nature in the works of Hans Purrmann (1880-1966), Werner Gilles (1894-1961) and Werner Held (1904-1954), who she became acquainted with on the island. In fact her early watercolours from Ischia are notably influenced by Werner Gilles´ style. This similarity, however, did not last long, as Rupflin’s independence eventually prevailed.

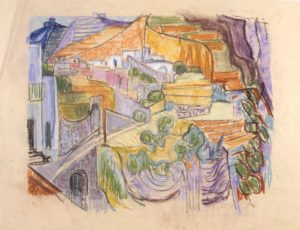

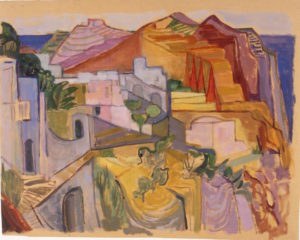

In terms of technique, her watercolours created in Ischia are less delicate compared to her early works. The colours are intense and often applied rather opaque in Gouache (L421). Nature as well seems to have changed: It´s not the landscape itself with its detailed structures and rock formations that she lays her focus on. Her images of landscapes are now dominated by brought areas of colours and combinations of brushstrokes causing the rather expressive character of her works. Nevertheless, the landscapes are not lost in the abstract, on the contrary, they are even identifiable due to the very precise pen, brush and even pencil studies Rupflin had executed en plain aire before she realised the rather large watercolours in the studio.

During 1953/54 in Ischia the trend towards abstracting art that stylized nature was strong. Even Anta was intrigued to follow, however, it had never been more than an inspirational source for her very own style, which was never fully abstract. This becomes very clear and wonderfully plausible in a series of five reproductions of a region in Ischia in watercolour, pastel, charcoal and tempera. (L420a-e) We find ourselves in front of a rising landscape with buildings and overgrown rocks in the foreground. To the left and right the view sweeps over houses, courtyards and walls towards distant mountains rising to the right. The two earlier watercolours reproduce this view in beautiful spaciousness – once with quite precise details, once only as a coloured impression – while the two later sheets in pastel and tempera – probably no longer painted in Ischia, but in the studio at home – show rather two-dimensional compositions, skilfully executed with lines and blocks of colour.

Another inspiration for these works may well have been the reading of Paul Klee’s book from 1956, whose quotation from 1917, “[…] that in art seeing is not as essential as making visible.” [1], became a firm motto for Anta and can frequently be found in her notes. This might ultimately explain the development of a series like this.

In any case, more and more rather abstract, sometimes completely non-objective compositions, emerged in the following period, which, however, often developed from various figurative motifs.

The artist’s last bigger journey finally brought her to Ibiza, where she stayed with a friend. One of the more than 60 drawings that were certainly executed in situ, dated on April 24th 1965 by the artist herself, clarifies the chronology of that trip. (L 661) Whether she later returned to the island again cannot be verified.

The often small-scale watercolours, pastels and drawings created there – executed with different coloured felt-tip pens of varying thickness – fundamentally differ from the works painted over a decade earlier in Ischia. They appear in a rougher, quicker, almost carefree manner. The large, wide landscapes of earlier times give way to smaller sections with a focus on the middle- and foreground, in which Anta reproduced nature in deep, expressive colours. These are truly late works, created with the compositional confidence and drawing experience of a long life. In addition, some very carefully composed gouaches with mountain motifs from Ibiza have survived, which were certainly created at home in the studio. Here Anta took the landscape to the edge of a mere composition.

After this brief overview of her most essential journeys, we will now attend to her stylistic development in more detail.

Although we don´t know when exactly Anta Rupflin spent time in Paris in the years 1925-31, nor how long she stayed there, we can be sure of the fact that it was here, that she laid the foundations for her later work. Inspired by the artistic aura of Paris, she produced a large number of typical academic drawings of nudes and portraits in charcoal, some of which she later developed into painted portraits. In addition, she learned painting on canvas from Mela Muter. Some exemplary portraits, still lifes and landscapes with oil on canvas have survived. Above all, however, she perfected her watercolour technique, which she had probably already adapted since meeting Hugo Schnegg in 1921, and was to remain her preferred technique.

Her development towards this preference had been so pertinent in the Paris years, that a very clear stylistic difference is notable between the early works created during stays in the coastal town of Collioure in southern France (L 313), in which colours are distributed rather graphically and the light paper tone retains an important effect, and the large, sovereign scenic cityscapes of 1930 in Tunis (L 349). This rapid development in style continued in the works created during an extended stay in Positano in 1933.

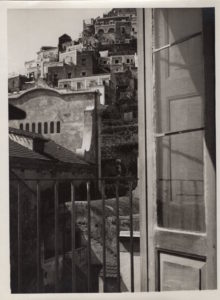

Artistically, this trip to Positano implied another important turn for Anta, which is mentioned in a later letter of her husband Karl Rupflin as well as further sources. Karl Rupflin wrote on April 24th 1936: “I realized this when I suggested photography to you. For the intellectual climate that is necessary for painting, is no longer present in our time, and painting is therefore a stroke of luck (if one sells) or a luxury (if one does not sell). The latter seems to be the general case today, thus I am dependent on claiming a part of your work power for myself” [2] Her husband’s hint about the need to support the family financially led her to work as a photographer from the early 1930s, an art form in which she already had been trained by Hans Kroher in Augsburg in the early 1920s. Now, however, she was officially employed in the studio of the photographer Dr. Moll in Munich and had a number of documented assignments. Amongst other destinations she was sent to Positano. Signed photographs from this period have survived, that, in terms of motif, are closely related to paintings of hers. (see L 253)

The photographic activity, but also frequent illnesses and several stays in hospitals in the 30s had kept her from intensive painting during that time. Only a few works can be attributed to those years.

A significant exception is the portrait of a distinguished lady in a striped blouse, sitting in an armchair (P 105). The three large preparatory paintings and drawings must have been executed around 1935 (105 a-c). Unfortunately, this portrait, her largest one in scale, lacks any written documentation from her side. The intensity and care she obviously devoted to this work, however, suggest that it might have been a commissioned piece. The exact date of creation, the lady´s identity, and why the portrait ultimately remained in the estate, however, remains unclear to this day.

Anta did not keep up her career of professional photography for long, which, judging by notes in letters and other sources, was already over by 1938.

As described above, the Rupflin couple spent their summer vacation in 1938 and 39 on the Dalmatian, nowadays Croatian island of Korkula, which they had visited once before in the late 1920s. Here they were caught off guard by the outbreak of war.

There is no information about what and how Anta Rupflin painted during the war years and the early post-war period. On the other hand, her letters repeatedly mention her illness and a long-lasting hospital stay with surgery in Weilheim. They also lead to the conclusion that – besides stay in Weilheim – she seemed to have spent most of her time in Bayrischzell.

Since she hardly executed any scenes of cities and towns in which she lived – only a few motifs from Augsburg (until 1936) and Essen (1932) can be found in her œuvre – it might be assumed that she painted and drew the multitude of still lifes, with flowers and various objects, at home, especially the extraordinary amount of works that show a characteristic motif of her’s: women.

Her female figures are of a rather dreamy, introverted nature. They are holding flowers, sitting or standing in front of a mirror, surrounded by a setting that is only very vaguely implied. Where they are depicted in pairs or even groups, they don’t seem to have a clearly defined relationship to each other. Her figures, often depicted from close up, usually take up the whole formats’ space.

Instead they are holding flowers, sitting or standing in front of a mirror, surrounded by a setting that is only very vaguely implied. Her figures, often depicted from close up, usually take up the whole formats’ space.

Very rarely she depicts single, male figures, but more often couples. This is undoubtedly a very personal theme that runs through all creative periods.

Moreover, she never depicted herself in one of her paintings. Her works always show different physiognomic character traits, although at times one can find a certain similarity in the slender appearance of the elongated oval faces, framed by blond hair, that appear in her works.

The depicted women, or rather the motif they stand for, seem like a mental portrait of the painter herself. Their appearance is in no way dramatic, but gentle, lyrical, rather calm. This fact was emphasised and very well met by the title Margaretha Krämer chose for an exhibition she had organized in 1996 at the Schaezlerpalais in Augsburg: “Longing for Poetry”. [3] Of course, portraits of women have not been a particularly rare motif in 20th century art, nevertheless Rupflin devoted herself to that particular motif – the woman as such, without consideration of her social position – in an extend which is not only unusual, but unique.

She certainly had to struggle hard to become an artist – to be a painter – as she had to do the split between her passion for creating art on one side and being a wife to the well-known fresco painter Karl Rupflin on the other, who held an important position in society as a professor of painting at various colleges and academies such as Augsburg, Berlin, Munich, Essen and founding director in Lahr. Thus, as a painter, she wanted to keep a low profile in public and therefore only once exhibited her works during her lifetime in 1959 at the Schöninger Gallery in Munich.

It is difficult to attribute Anta Rupflin’s art to any specific artistic movement. Particularly since she did not join or feel related to any specific group herself and moreover only temporarily adapted certain stylistic traits of the few artists, who inspired her to some extent, such as Hugo Ernst Schnegg, Mela Muter, Werner Gilles, or Hans Purrmann.

She got mentioned in Rainer Zimmermann´s work Expressive Realism: Painting of the Lost Generation. [4] A small part of her work might certainly be classified as such – especially the landscapes, painted in Dalmatia shortly before the war, or the late landscapes painted in Ibiza, as well as some of the late flower still lifes. For the majority of her works, however, this classification does not seem entirely suitable.

How very independent her work is, and how difficult it is to classify it clearly, had also been a subject to Erich Pfeiffer-Belli´s insightful review of Anta Rupflin’s exhibition at Schöninger in Munich, who wrote the following article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung on February 12, 1959:

„Eine sympathische Begegnung mit der aus München stammenden Malerin A.R., die sich den Atelierwind interessanter internationaler Künstler um die Nase hat wehen lassen. Sie schreibt somit verschiedene Handschrift, ohne den eigenen Duktus ganz vergessen zu lassen. A.R. ist in vielen Sätteln sicher – naturalistisch hier, abstrahierend dort – farbig kultiviert und eindringlich und stets darauf bedacht, der eigenen Entwicklung den Weg wieder freizumachen. So bleibt sie ständig um Selbstdarstellung bemüht. Bemerkenswert die Ernsthaftigkeit der genauen Arbeiterin, ihr Geschmack, ohne geschmäcklerisch zu sein. Ein offenbar künstlerisch empfindsamer Mensch, der entschlossen ist, es sich nicht leicht zu machen.“ [5] Pb

“A sympathetic encounter with the Munich painter A.R., who had been taking a breath of air from the studios of distinguished international artists. Thus she shows different handwriting, without letting go of her own style completely. A.R. is confident in many Styles – naturalistic here, abstract there – sophisticated and powerful in colour and always anxious to clear the way for her own development. Thus she constantly remains concerned with self-expression. Remarkable the sobriety of the accurate workingwoman, her taste without being stuck in it. A clearly artistically sensitive person, determined not to make things easy for herself.” [5] Pb

This was written, though he did not know the impressive late work of the painter at all.

Dr. Gode Krämer

[1] Klee, Paul: Das bildnerische Denken, Basel 1956, p. 14.

[2] Letter from Karl Rupflin addressed to his wife

[3] Dr. KRÄMER, Margaretha (Hrsg.): Kat. Ausst. Sehnsucht nach Poesie, [Anlässlich der gleichnamigen Ausstellung im Schaezlerpalais, Augsburg und in der Galerie der Landeszentralbank München, 1996], Augsburg 1996.

[4] ZIMMERMANN, Rainer: Expressiver Realismus. Malerei der verschollenen Generation, München 1994, p. 437-438.

[5] Review of Erich Pfeiffer-Belli in SZ vom 12.Feb.1959